In 1973 a tomb was unearthed in the Hunan province of China, which was originally sealed in 168 B.C. In it were the bodies of the Marquis of Dai, his wife, and his son.

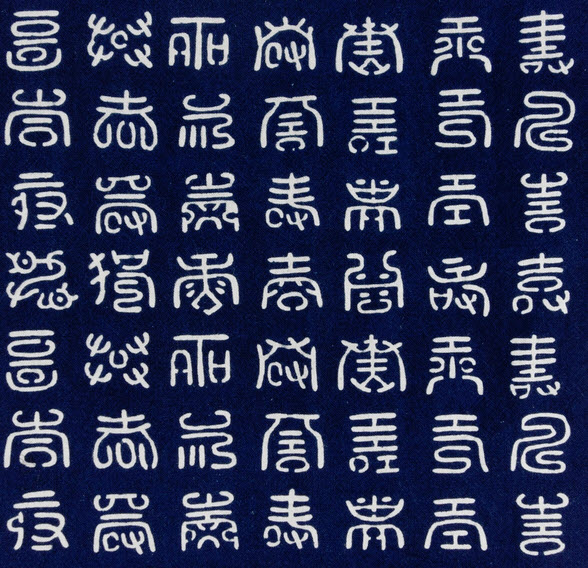

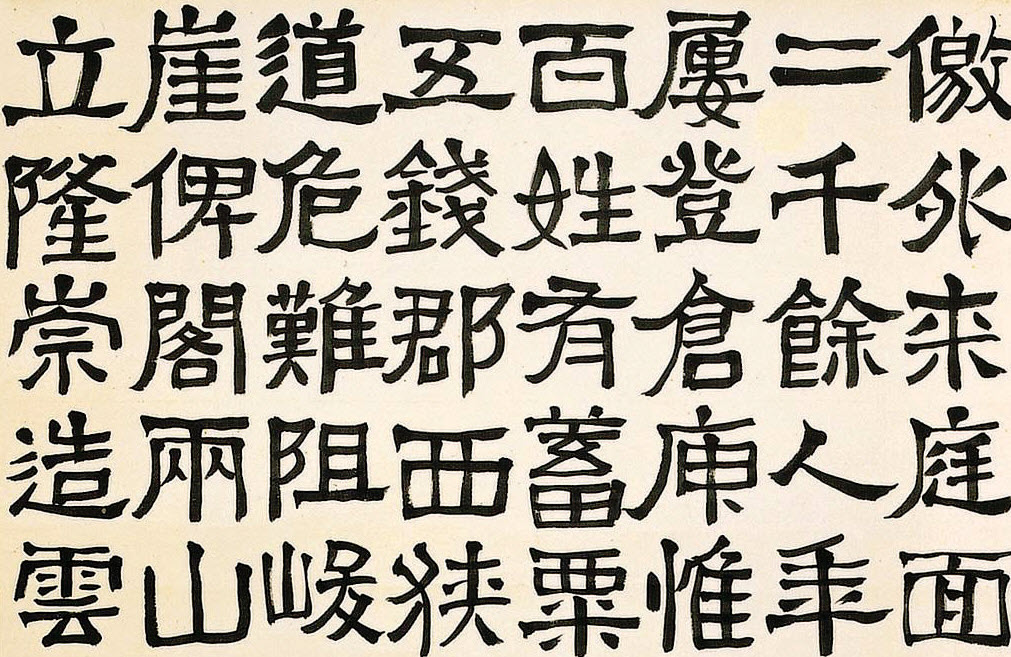

The tomb also contained thirty manuscripts, including two versions of Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Jing, written in different scripts. One in clerical script, and another in more formal, seal script. We would probably think of these as different fonts.

There were also fifteen medical manuscripts including methods of diagnosis, a treatise on meridians, how to create medicines from herbs, dietary manuals, and a manual for childbirth.

But the manuscripts I find intensely interesting are the drawings called the Daoyin, depicting various exercises. These are the origins of Qi Gong and Tai Chi.

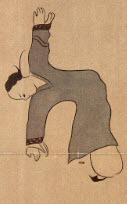

Here is the original scroll:

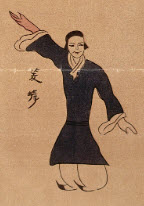

Thanks to scrupulous study, and the miracle of Photoshop, we have a fairly complete image of the drawings.

Each exercise comes complete with colorful names like Measuring Worm, Bend and Gaze, Duck in Water, Upright Swivel and Snake Wiggle.

Yoga folks will recognize the Reverse Triangle:

You can see early versions of Tai Chi moves. Check out this one, which I think looks like Flying Diagonal:

And if you ask nice, I’ll bet Sandy will show you some of the stick form she learned while down in New Mexico.

It’s helpful to know the history of the things we’re practicing now, from the earliest Daoyin forms shown here through the animal frolics and eventually to the “modern” (OK, only several hundred years old) Tai Chi forms we’re just learning. The other day Roy observed during class that the Tai Chi I’m teaching today is very different from what I was teaching five years ago and has very little semblance to what classes looked like 10 years ago. It’s all true. If anything, this history shows us Tai Chi evolves.

When you’re learning the form, it is important to be precise. Just like learning the piano requires learning to play scales. It takes a while to get the movements into your body so you can do them correctly without effort. It doesn’t matter if you study the Chen form, the Yang form, the Sun form or Chen Man-Ching’s form. They are all good, but you need to stick with one form and learn it correctly down to the last itty bitty detail. Your learning path should be a mindful, intentional concentration that constantly evaluates, refines, and improves your from until you make it yours. It should be reliably repeatable. That’s how your body will absorb the form and move it into your muscle memory.

As you practice and practice, the form should move deeper and deeper into your body. That’s why we call it an internal art. Your core is what’s important. Are the precepts proper and well founded? As Bill Wallick is fond of pointing out – the important thing is the principles.

Chen Man-Ching’s five principles are good to keep in mind:

- Body upright

- Mind in the Dan Tian

- Separate yin & yang

- Beautiful lady’s hands

- Relax